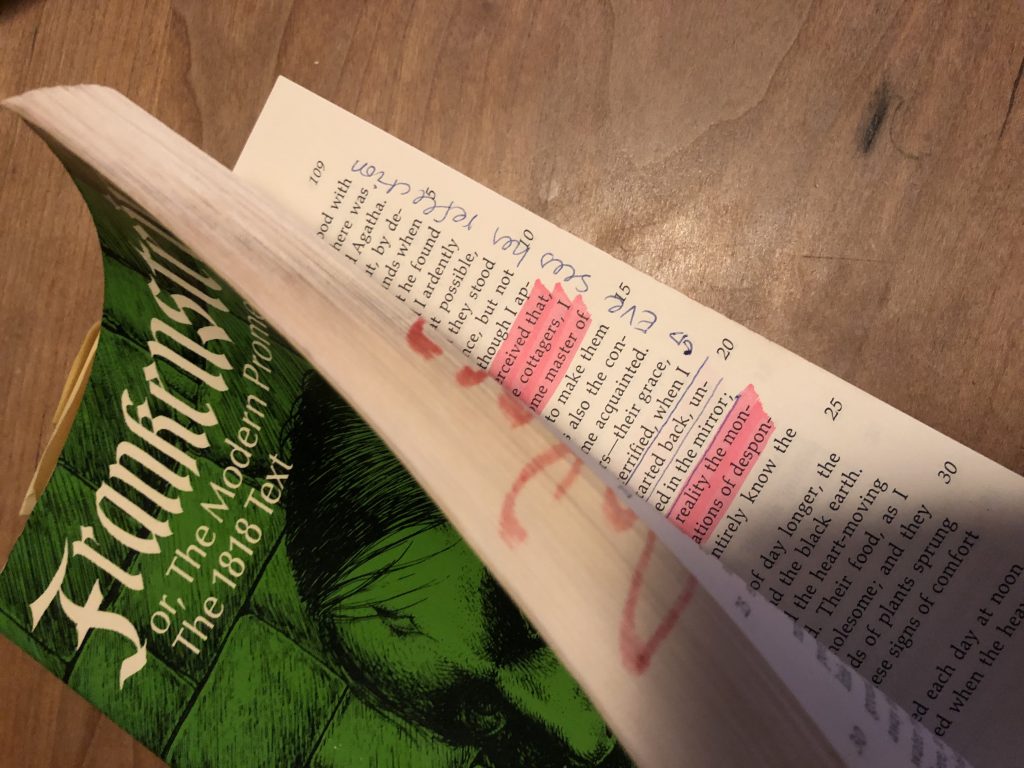

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is probably the first book I loved as a scholar. I had loved many books before that one as a reader, but Frankenstein, which I read for the first time in high school, was a book I came to love through working with it. When I think about how that love was generated, there is an obvious physical practice that comes to mind: annotation.

I think part of what excited me about annotating the novel was the fact of ownership. 10th grade was the first year I went to a private school in my town where we owned the books we used in class. Which meant not only that we were allowed to write in them, but that we were supposed to write in them. And because it was an elite school, there was no mechanism in place for selling books back; you bought them and you kept them (a struggle for my parents, no doubt, and so many connections here to the OER pathway I currently travel). I can’t tell you the transgressive joy I felt when I selected colored highlighters to code to different themes in my book. In my book. The act of annotation somehow transformed that novel into something that was mine.

As I worked over the years with Frankenstein, my marginal notes became increasingly interested in the marginalization and feminization of Victor’s creature. My marginal notes revealed a radical novel inside of Mary Shelley’s original radical novel. And I felt a sisterhood with Shelley, and with her creature, that truly was powerful.

In graduate school, marginal annotation was the lifeblood of my scholarly existence. Samuel Purchas was a 17th-century British armchair traveler who wrote pamphlets to encourage white settlement in the Americas. I annotated those pamphlets until the texts became illustrations of the violent roots of colonial exploration. Reading became an act of resistance, a project of revisionist history aimed not at whitewashing the past, but revealing its brutal racism.

I like the idea of a text’s margins being a space to amplify the marginal subtext, make visible the marginalized experience, or subvert the dominant discourse with critique. And I like that the act of annotating is an empowering one, one that ascribes ownership over the text through the (possibly) democratic act of reading.

The Marginal Syllabus, the brainchild of scholar Remi Kalir, plays with all of this as it invites scholars to annotate articles on the web together. Using an app called Hypothes.is that allows for public annotations to be layered on top of any website, scholars can meet up in the margins of an article and trade ideas, critique, and commentary:

- The Marginal Syllabus collaborates with authors whose writing may be considered contrary – or marginal – to dominant education and schooling norms.

- The Marginal Syllabus hosts and curates publicly accessible conversations among educators that occur in the margins of online texts via open web annotation.

- The Marginal Syllabus mediates educator collaboration using Hypothesis, a technology that was neither developed nor initially intended for use in a learning context; educators use an open-source technology developed by a non-profit organization that is marginal to commercial edtech.

We can see the puns between the margin of a texts and the margin of a culture, and the assumption that annotation can be a radical upset to the status quo.

But margins are contested spaces, perhaps moreso than texts. Author Audrey Watters, a radical voice in education for sure, went out of her way to block annotations on her website. At the time, Watters was openly licensing most of her work. About the blocking of annotations on her site, Watters wrote,

one of the accusations lobbed against me when I blocked annotations here was that I was attempting to exert some sort of “authorial control” over my work. Wrong. I was exerting control over my website.

Even if Frankenstein were still under copyright, nobody would argue that my copy isn’t mine to mark up however I wish. But when I read an article on Watters’ website, I am somehow entering a space that is her own, where the text there hangs somewhere in between the author and the reader. The act of reading and commenting doesn’t make that text mine in the same way that reading and commenting made Frankenstein mine. Printing it out, or copying an openly licensed version of her article onto my own site, that would do it. But on her site, it’s hers as she conceived of it.

At first, this confused me. How did this fit with the kind of open learning that I was interested in doing with my students? Around the same time as I was pondering Watters’ choice to prevent annotation at her site, I was teaching a course in First-Year College Composition. Many of my students were creating their own blogs. And we were using Hypothes.is a lot to comment on each others’ work and on class readings. Well, one of my students was a shy young woman who took a brave and calculated step to write about her own story: how she came out as a lesbian to her conservative rural farm family just a few weeks before our semester began. It was a sad, honest, and hopeful essay, beautifully written. She was proud of it, and happy with her decision to post it on the web.

We all know that social media can be vicious, and that being a lesbian (and/or a person of color and/or any number of other marginalized identities) can mean that you’ll suffer far more than a fair share of abuse, threats, and trolling. But suddenly I realized that there in the margins of her own site, her domain of her own, annotations could appear that would attack her for who she is, and who she chose to reveal on her website.

I love that scholars routinely show up in annotation flash mobs to correct gross and intentional errors in online articles that call climate change a hoax. That feels like a way that the margins are leveraged to challenge centralized power and create a narrative of resistance. But like open education, we should expect that once the power of margins are revealed that they will be co-opted by the powerful to reinscribe that power.

When I spilled a bunch of coffee (my husband spilled it! I don’t even drink coffee!) on my copy of How Humans Learn, it only magnified my love for the book. Marked up with annotations and now stained by coffee, this is nobody’s book but mine. It’s written just for me, because the marginalia recasts the whole text for someone who is about to help launch a learning community for 70 faculty and staff members at my university. But now I wonder about ownership. And I wonder about rewriting, and I wonder about how we can be sure of where the margins are and where the center is when power is so provisional.

When I think about trying to work in the margins; design learning ecosystems that value marginalized voices; imagine educational ecosystems that are decentralized or de-centering, then I wonder how we will avoid having those margins weaponized back at us. Once we develop a sense of comfort in the margins, and that comfort becomes power, and that power consolidates, who will be pressed out?

I don’t have answers to any of this. I generally use my margins for questions.

Question

What are some ways that you can imagine students or scholars using public digital annotation to speak truth to power? What are some ways that you can imagine scholars or students being silenced by public digital annotation? How do the margins of the internet matter for learning and/or for the public good?