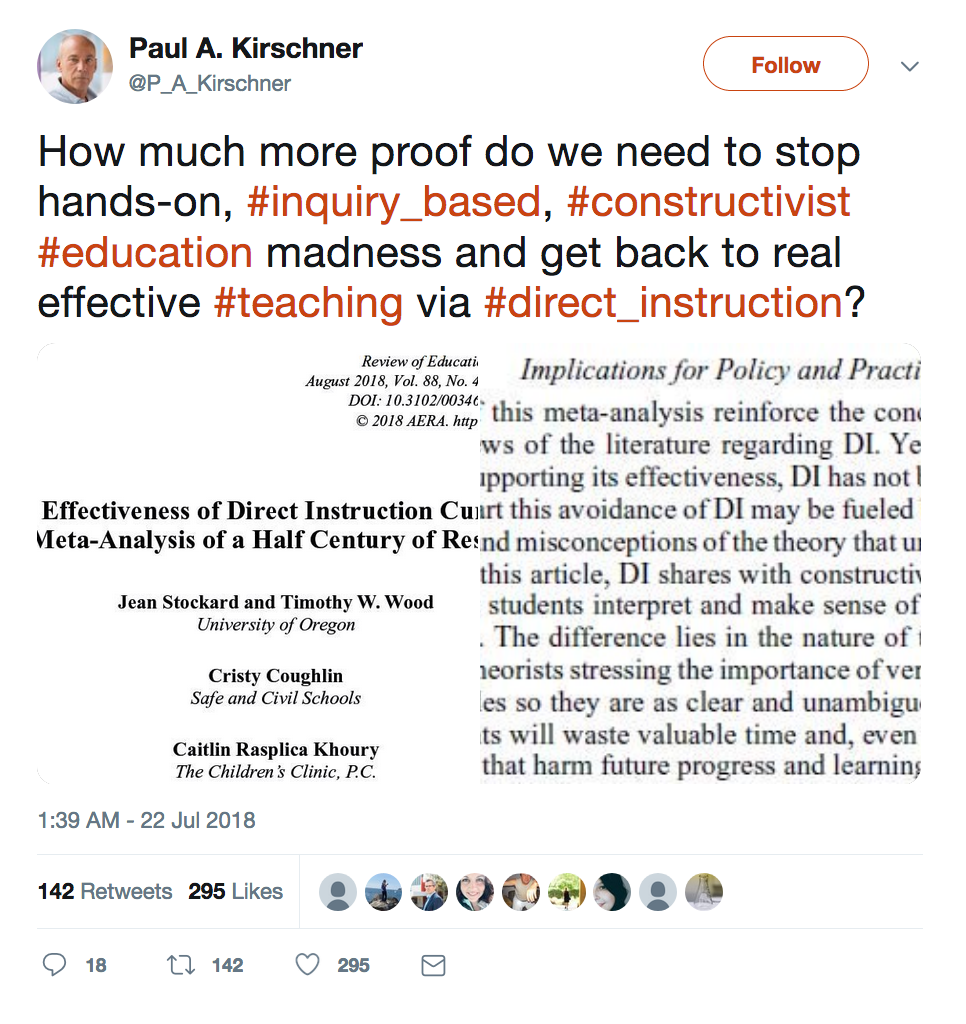

Paul Kirschner is a professor at the Open University of the Netherlands and a leading educational psychologist. This summer, he tweeted this:

In an interview about the tweet, he continued:

The only thing I accept as ‘true’ is what is supported by high-quality research.

I am a researcher. I suppose my Ph.D. in English qualifies me to say that. I know I spent a lot of hours researching for the books that I published. And those books were filled with “evidence,” which was something I was incrementally taught to generate through the course of my many years of secondary school and undergraduate studies in literature.

Before I unpack a few of the critiques that Kirschner has about constructivist teaching, I want to spent a minute talking about “evidence.” In my field, evidence is the key to writing an effective research article about a novel. But the “evidence” is markedly different than the kind of evidence one might produce in a science or social science project. In literature, we build evidence for an argument not by determining through testing that the argument is “true,” but by locating patterns in a text to demonstrate how a certain reading is possible. And we look for historical patterns in how readers have interpreted works or in how texts have mattered to the world in order to understand the multiple ways that literature and society can inflect each other. If I argue that Victor Frankenstein’s monster is a metaphor for how scientific research without attention to ethics is monstrous, it is not because that is true, but because that is a possible interpretation of the text that can be supported by a close reading. I might produce pages and pages of evidence from direct textual quotations and from scientific and philosophical writings of the period, but I still will not be making an appeal to truth. I will be making an appeal to possibility, raising a question rather than answering it.

This is because literature and the arts and science and social science each have different epistemological frameworks, where what counts as evidence and truth are different. Because the field of education is a social science, the evidence that counts in that field is often produced using quantitative methods, which are far different from the qualitative methods that are more familiar to those of us in the Humanities. When I look for patterns in Frankenstein to build an argument, I am more interested in opening the text to increased questioning rather than solving a problem or stating a singular conclusion. And this is different again from the kinds of patterns that we track in social sciences, where we code qualitative data in order to build conclusions about the way things work. Or, in Kirschner’s case, what kind of learning “works.”

Kirschner is critiquing constructivist learning, which, to define it too quickly and loosely, is an approach that centers experience and student agency in the learning process (and the instructor just becomes a guide on the side). He is setting it up as an alternative to traditional direct instruction–DI– by a teacher (we sometimes call that the sage on the stage). And he is citing a critical mass of research that shows that direct instruction is what yields the best learning for students.

There’s lots of discussion about whether constructivism or DI is better for learning. But not remotely enough discussion about what learning is. The cognitive load theory that Kirschner explains and explores centers on how memory relates to learning, and in particular, how it’s different for beginners and experts in a given field. Beginners rely on short-term memory to move information slowly into their long-term memories where they will ultimately be able to work on the kinds of complex concepts that experts can address. But because short-term memory is notoriously inefficient and can be overwhelmed easily, there are best practices associated with moving information into short-term memory in a way that will ultimately help it stick. We can hone these best practices into rules if we want. For example, banning laptops and cell phones from classrooms can assist with recall because studies show both that distraction impedes short-term memory and that handwriting notes, as opposed to typing them, improves it.

I quite willingly offer up the fact that I am not an expert in any of this. And I wouldn’t even begin to quibble with any of the points from the studies that Kirschner mentions or with his point that direct instruction is effective at helping students learn. But helping them learn what?

If we think of learning as the ability to remember information, and to understand it in a way that allows one to apply, critique, and develop it, then I can accept that direct instruction is sometimes perfect (of course, so much rides on the instruction that we can easily imagine from our own pasts with select horrible teachers that it is also sometimes imperfect). Generally, we can tell when DI is working by assessing, or testing, the first step– do students remember? And sometimes we test the second step– do students apply? We generally don’t test the critique and develop steps, since we leave those for when they are experts.

So the problem is that we are looking mainly at recall and perhaps also at application of knowledge. But this is not all there is to learning. This does not include how to generate intellectual interest in a question, how to frame that question, or how to hone it. This does not include asking (not answering) why something should be or could be learned. This does not include learning adjacently as connected subjects emerge. This does not include refiguring an area of inquiry when a dead end stops you cold. Actually, many of the ways I learn as a scholar have little to do with recall and application, and that is true even when I am learning a new thing.

I don’t mean to reject direct instruction. That’s not my project here. What I do mean to do is to suggest that constructivist approaches, including open pedagogies, aren’t an alternative to direct instruction. They are epistemelogically distinct. Literature is not an alternative to science. It’s a different lens on the world.

An open pedagogical approach believes that laptops should not be banned from classrooms. Here are two reasons:

- Learners are not blank slates when they arrive to classrooms, so for some learners, laptops may be necessary to help them access and work with the content;

- Laptops are tools, and all tools can be used in a range of ways, so unless you know your learning goal and how a tool will be used, you can’t know if the tool would be a help or a hindrance.

When we ask whether there is evidence for something related to learning, we are presuming that we all agree 1) what learning is and 2) what constitutes evidence. I contend that “learning” is broader and messier than what we generally assess, and also that “evidence” has been reductively equated with quantification and with the assumption that environments in education are controlled. At the core, I think the biggest problem is that we forget that humans aren’t just giant brains walking around: we are also a jumble of social contexts, emotions, and circumstances. Constructivist approaches don’t have to replace direct instruction. But they do gesture towards other lenses that we can use to examine how learning happens.

HEY, SO I just found this page in my drafts folder. I was supposed to finish it and make it part of the keynote. But I got depressed and stopped writing it. So tired of it all. Then I forgot it existed. I just found it when Ken Bauer Favel jogged my memory, and I wondered if I dreamed it. I didn’t dream it; but I am also not going to finish it. So there.

Questions

- What constitutes “evidence” for learning? What do you think? Does your disciplinary training influence your thinking? Are there parts of learning that can’t be measured at all?

- How has the increasing attention on evidence-based teaching and on program and institutional assessment helped you improve your pedagogical practice? And/or how has it inhibited it?