To follow along with the text of this presentation, view the Google Slides version of the talk as I give it: http://bit.ly/rethinkingdistance.

Here is the video for the keynote. The transcript follows below.

[This version below has image descriptions, so may be the best version if you are using a screen reader.]

Recently, I have been spending a week each summer on Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine. It’s a rustic place without much electricity, no cars allowed, a tiny population (about 65 hardy Mainers). I go there and try to stop talking, which is easier for me than you might imagine if you know me! I like not only being quiet, but thinking about being quiet. A few weeks ago, I composed the first draft of this keynote on Monhegan, as I was reading Sarah Maitland’s 2008 A Book of Silence, which is one-part a memoir of living quietly in some of the world’s most silent spaces and one-part a cultural history of silence.

I was struck by this quote from Maitland. Because there I was, chasing solitude and silence on a remote island, working on a project about distance. I was struck because distance and solitude and silence all seem so intertwined. They all conjure up the sense of going away from, retreating from: people, noise, communication. But Maitland made me pause. Maybe it isn’t that these things are retreats or losses. Maybe it’s not about a lack of something or leaving something or losing something. Maybe there is a qualitative difference between language and silence. And between distant and face-to-face. But maybe that difference is not one of opposites, but one of relationality.

[We will pause here to do a silly activity where people across the room wave at each other.]

So now look around this room and ask yourself, “Who here is at a distance?” The answer is everyone. Everyone is separate from you, but everyone in this room and outside of it could be mapped into your world and become connected. So I started thinking, what really is the difference between learning at a distance and learning face to face? And if distance holds inside of it the seed of connection, what does that mean about how we think about the world wide web, this connective technology that we are only beginning to understand in education.

I hope you will indulge me for just a few more minutes in thinking abstractly about distance before we really try to parse out what we might think about distance education. As a literature scholar, I automatically move to metaphors. So many of the ways that distance functions in our everyday lives is in helping us to make sense of our relationships and emotions. Whether something is near or far has little to do with objective measurement and everything to do with how we feel and what we choose to compare it with. Having friends across the globe can make you feel every mile as a vast unmapped chasm as you miss them, but can also make you feel every mile as a possible route to connection. Thoreau explained it this way, “Nothing makes the earth seem so spacious as to have friends at a distance; they make the latitudes and longitudes.”

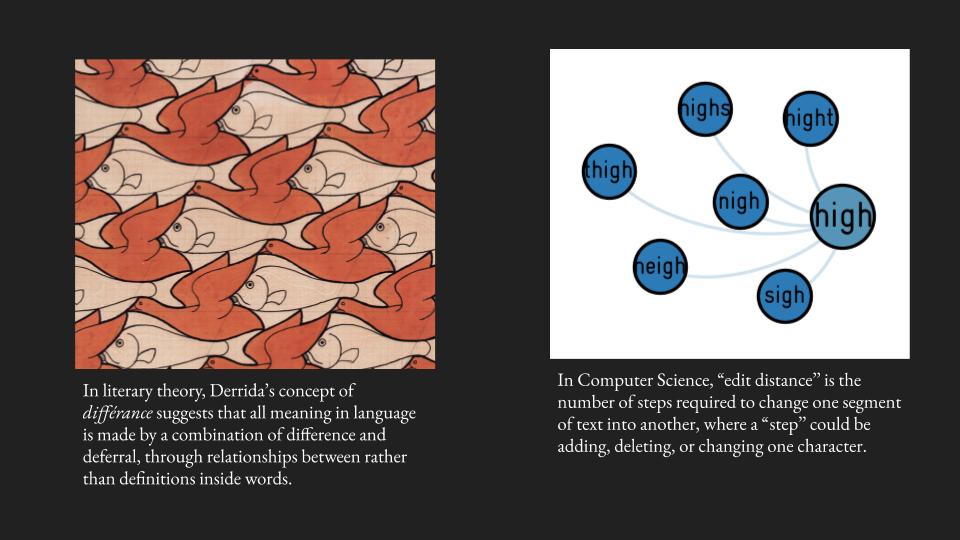

In literary theory, Derrida’s concept of différance suggests that all meaning in language is made by a combination of difference and deferral, through relationships between rather than definitions inside words. The meaning of the word “cat” is not inherent in the word itself, but in the way that we know it to be a different word than cab or hat. It’s through the relationships with surrounding words and contexts that anything gets its meaning.

In Computer Science, “edit distance” is the number of steps required to change one segment of text into another, where a “step” could be adding, deleting, or changing one character.

In both cases, we can see that distance isn’t at all what is remote or away: it is that which is right here, adjacent and related, but different. That which is connected.

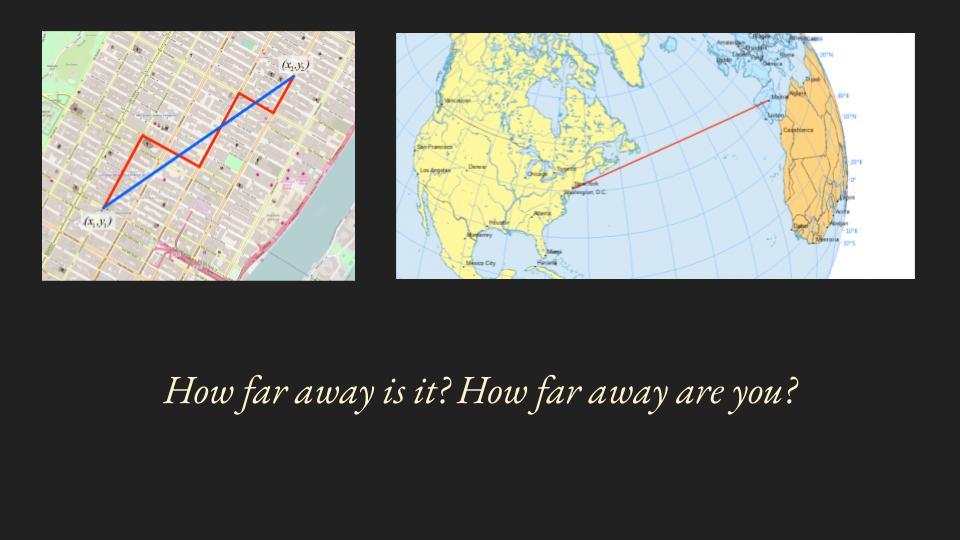

But of course the maps we make aren’t all in metaphors or code. When we think of distance, what we mostly think of is measuring geographic space. We use calibrating tools, compasses, to plot our points and calculate. But still, how far away is [A] from [B]? We can measure “distance travelled,” as [A] winds around tables and chairs. We can map the straight line Euclidian distance. We can calculate the geodesic distance and consider the curve of the earth that always bends us even when we feel like we are going straight. The point is that the objective distance will change depending on the tool we select, the context for our scientific observation, the disciplinary backpack we carry with us on our map quest.

So when we think about “distance” learning, and imagine that it means something, I am not sure that it does mean some thing. It may more likely mean many things, both because distance itself, even at its most scientific, is still subjectively understood and experienced and deployed, and because distance, when yoked to education, is a complicated, technology-infused mash-up of human separation and connection.

And of course the word “distance” when used in “distance learning” is also inflected by the history of distance education, from the correspondence class through our contemporary online landscapes. One of the first ads that ever ran for a distance education course was for Mr. Caleb Phillips’ shorthand course, a course offered via mail in the early 1700’s. For those rural colonists who wanted to learn shorthand without the expense or radical effort of riding into Boston for face-to-face classes, they could be as “perfectly instructed” as those from the city by taking the correspondence class. Two things resonate with me, sitting here three hundred years later. First, the idea that people outside of cities or without means or a certain background could still gain access to learning. And second, this learning would be a perfect match to the learning that others were able to do face-to-face. We still hear both of these arguments for and about distance ed today: it increases access and is “just as good”– in fact just the same!– as traditional instruction.

But the history of distance education contains some other seeds that might seem familiar to us now as well. A hundred and fifty years after Phillips’ first ad, and the distance education market has exploded. Whole schools had cropped up to meet the growing demand for correspondence-based education. The largest private for-profit school based in Pennsylvania, the International Correspondence Schools, was founded in 1888 to provide training for immigrant coal miners aiming to become state mine inspectors or foremen.

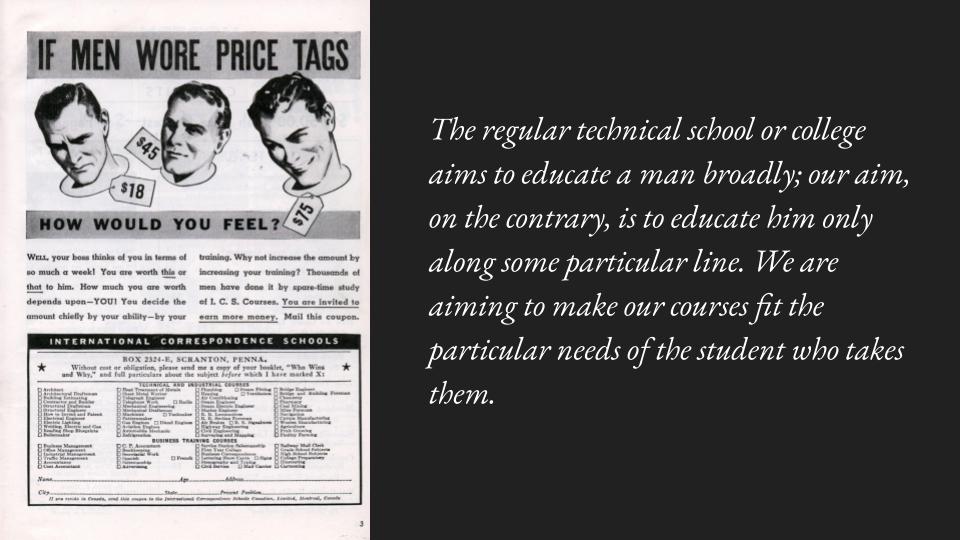

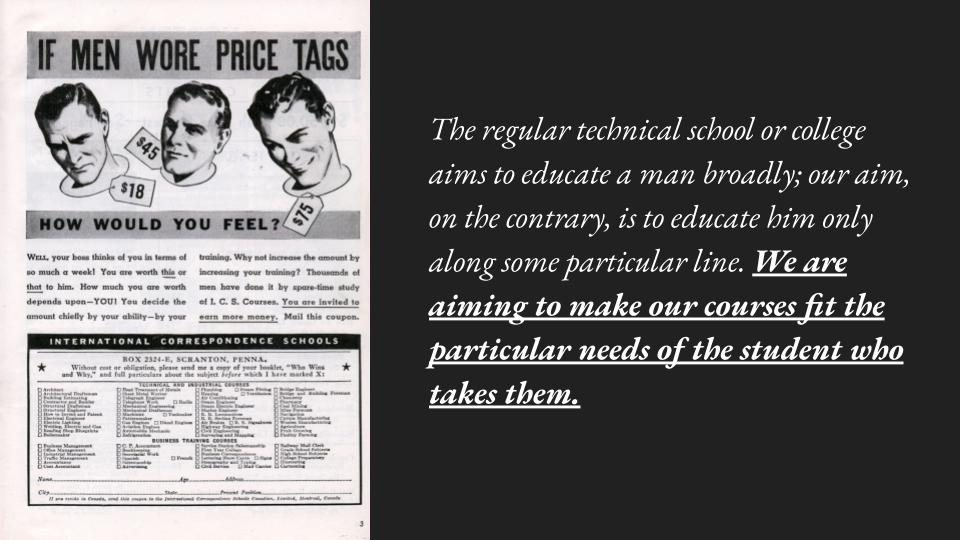

It enrolled 2500 new students in 1894 and matriculated 72,000 new students in 1895. The growth was due to sending out complete textbooks instead of single lessons, and the use of 1200 aggressive in-person salesmen. (Wikipedia). What we are seeing is the moving from skills-based training to jobs-based training, an easy hop to understand. And the correspondence moves from an interactive dialogue between a teacher and student to a model where students can self-progress through larger curricular chunks at their own pace. And anyone who has read Tressie Macmillan Cottom’s Lower Ed, a brilliant book about the for-profit higher education industry and the complicated way that it fails to deliver on promises especially to poor people and people of color, will note the familiarity of the effect of a robust sales pitch on a demographic of learners who are precariously dependent on the whims of an exploitative labor market. This ad shows the growing connection between labor markets and learners, and the shrinking distance between the value of what you know and the value of who you are.

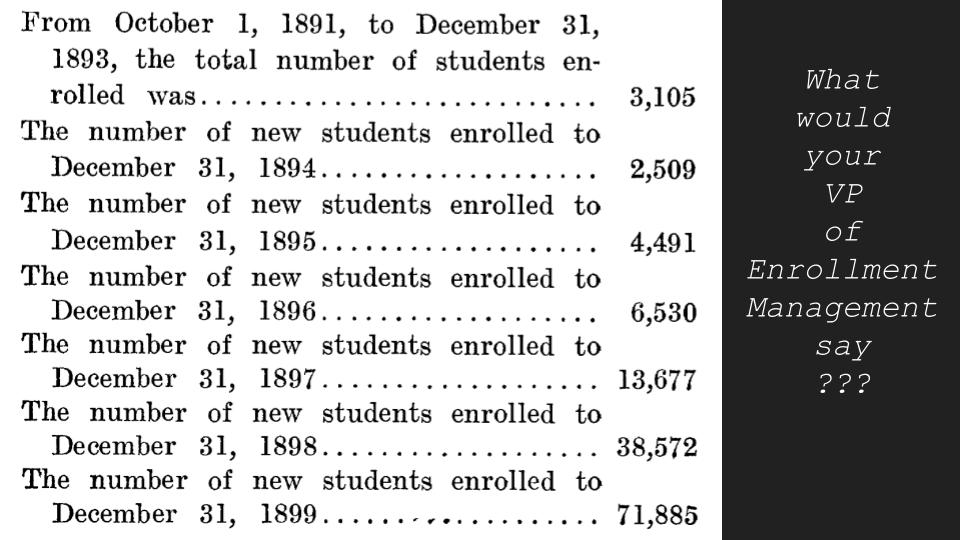

By 1906 total enrollments at the International Correspondence School had reached 900,000. (Wikipedia) You can see from this chart that it’s early years demonstrate its promise as enrollments begin to double and then eventually explode. Now this depends where you are, but those of us not at elite institutions, and particularly those of us in regions of the country facing demographic slides in young adults, we could hear the saliva begin to fall from the mouths of our desperate enrollment managers if these were our Admissions trends. In public instituions, as state support has declined (or not recovered after the 2008 recession that decimated so many of our school’s budgets), we have grown increasingly dependent on tuition to operate. My public regional university in New Hampshire is about 9% state funded. And each year, there are fewer and fewer young adults in the northeast to apply to college. Our enrollment managers are desperate. They are increasingly looking to job training, private partnerships, distance education, and adult learners to reach new markets. But of course, historically, we can see, these are actually old markets.

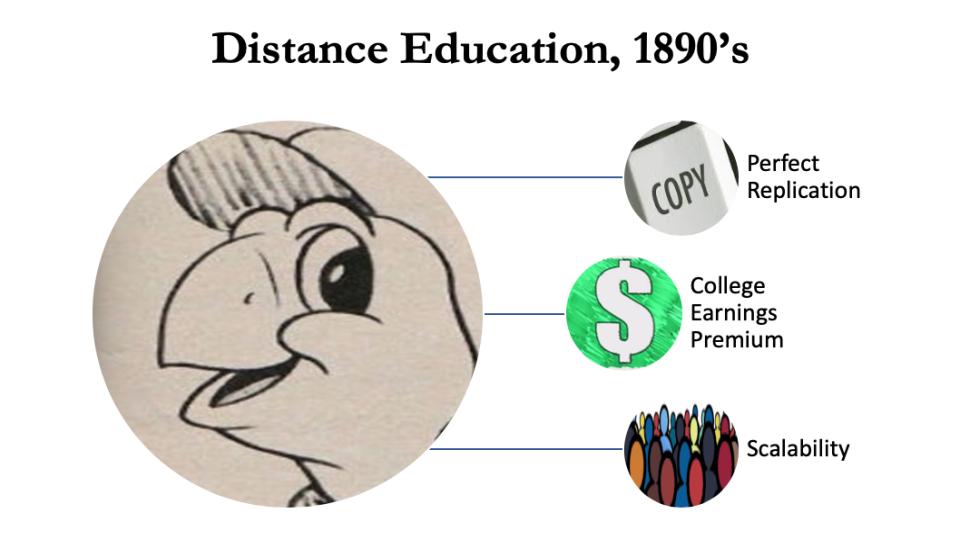

You may recognize Tippy the Turtle on the left there. He was the “draw me” turtle that you would have to send in to gain admission to a correspondence school art course that advertised heavily in magazines I read in the 1980’s. Audrey Watters has a wonderful piece where she traces the history of distance education more extensively than I do here, and spends rich time on the “draw me” era and its connection to the rise of MOOCs. I’m using Tippy to delineate three of the key characteristics of distance education that have been held over from the earliest boom in American distance ed through today’s dominant rhetoric around distance learning.

First, the promise that distance education is just as good, valid, and high quality as f2f instruction– indeed that it is really no different (“get the same [insert college name] education with this online degree!”). Second, the promise that your earning potential, what we sometimes now refer to as the “college earnings premium,” will increase if you take this course of study. And third, that distance education is scalable to provide maximum access to learners and maximum enrollments– and revenues– to institutions.

I am sure you have already guessed that I take a critical approach to thinking about these three qualities. We might call it the Sad Tippy Critique. Ultimately, I will argue that we undermine a truly learner-centered vision for distance education if we subscribe to the “perfect replication model.” But I want to start by thinking about the College Earnings Premium as a way of beginning to gesture more pointedly towards my critique, and therefore towards what I would consider to be a more humane, just, and promising vision for distance education as we move forward.

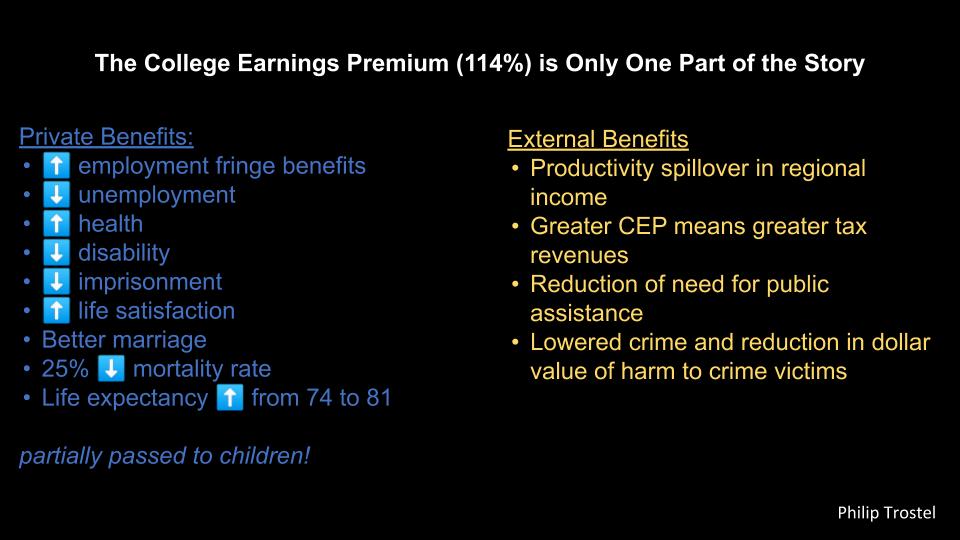

If you get a college degree, studies show us that you are likely to make on average 114% more money than you would have made if you didn’t get the degree. College degrees more than pay for themselves this way. Same with Associate’s degrees, where the costs and premiums are lower but still proportionately a great deal for learners. Of course, the news gets worse if you take out significant loans for college and then never get a credential, therefore forfeiting the lion’s share of the CEP. But you likely know all of this because Admissions officers like to make it known that if you go to college you will MAKE MORE MONEY. In fact, if you were a line drawing of a white guy, you would see your attached price tag go up in real time as you graduate!

But the CEP is a reductive way to measure the benefits of college. CEP measures only what economists call “private market benefits.” But there are many more private benefits than CEP– like the fact that you are more likely to get better fringe benefits at your job if you have a college education. More notably, there are other benefits that are less directly tied to markets. Your health will improve, you will be less likely to become disabled, less likely to be imprisoned, more likely to enjoy your life, have a better marriage, and live longer. And you will partly pass these private benefits on to your children, whether or not they attend college!

And then we can also look at benefits that go beyond the individual. There are a host of economic and quality-of-life benefits to regional communities when more residents attend college. None of these private or external benefits, no non-market benefit, negates the college earnings premium. But what it shows is that when we think of college as just an individual good tied to earnings, we rewrite the facts about what is so powerful about higher education– in particular public higher education.

So the question I want to ask is, how do we need to rethink the concepts of distance, the history of distance education, and the current state of online learning in order to expand the paradigm so that it offers more of a vision for higher education that serves both individual needs and the public good?

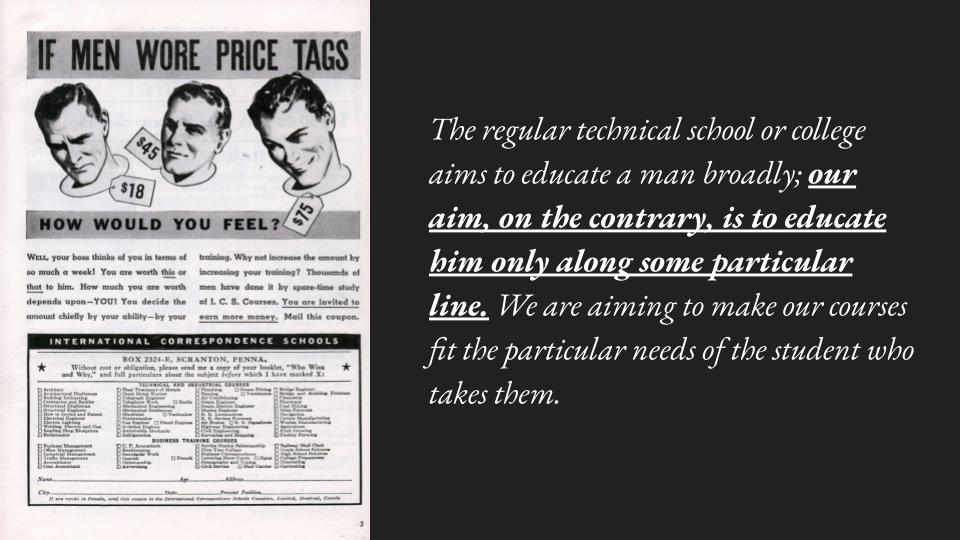

As a way of looking forward to today’s shiny online learning environment, let’s go back a moment to the turn of the last century ad that promised that specific-job oriented training. As distance ed became a way to train for the competitive human pricing market, we saw a striking thing happen. “We are aiming to make our courses fit the particular needs of the student who takes them.” (In this case, coal miners.) They were personalizing their courses. But of course, following Cottom, I would say that this personalization is about tailoring humans to fit markets, not tailoring courses to fit humans.

This legacy of selling “personalized learning” that turns workers into commodities to feed the specific needs of a labor market is a trajectory that is thriving in today’s online learning environment.

Here is part of the definition of “personalization” from Wikipedia:

One obvious thing I will point out here is that the “person” is mostly missing from this definition of “personalization.”

For sure the most brilliant scholar writing on the dehumanization of personalized learning today is Audrey Watters. As Audrey points out,

She goes on to reflect on how early “teaching machines,” designed to scale personalized learning and wrap it in with the push to market technologies for education, became a whole industry based on “the atomized individual moving through atomized content modules filling out little circles and pressing little buttons.”

So we have this intersection, where computers and job training and scalability mix into this personalization cocktail, and the result is… a particular line.

Particular. Custom, individual, one of a kind…line– the most ubiquitous, unilateral, boring, and scalable of shapes. The personalized line: an oxymoron.

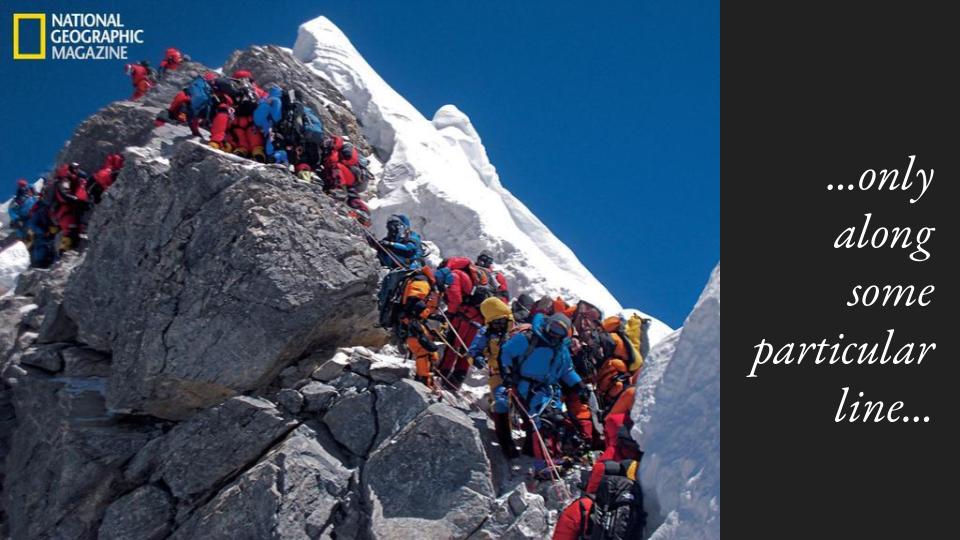

The trajectory and qualities of this line are worth considering. The line seems to be either left to right or bottom to top. The focus is on the summit, getting people up one at a time. At the top of the summit? Revenue success: for the students who achieves the CEP or new job, or for the institution that sold the course or shored up its reputation to increase its selectivity or enrollments. Instructors in the original push-button machine learning world, or in the more original correspondence course, worked to support individuals or groups, but individuals and groups were unable to work together. The pony express, the USPS, the old-school offline computer did not encourage collaboration, only call-and-correct.

Like this line up Everest, the focus was on individual achievement, and stopping to help a fellow climber could mean sacrificing your own ability to survive in a fundamentally hostile environment.

(I’m problematically ignoring some of the obvious problems with the Everest jam as a metaphor– since precisely nobody makes it up Everest along, and how many Sherpas have literally carried how many men and women up and down this mountain? A complex addition to the economics and social power structures of the mountain.)

Not only do we not think creatively enough about what distance is, we also don’t do enough thinking about how the technology that allows us to go online could or should change the landscape for distance learning. I don’t need to tell anyone here that the internet is a meaningful invention in the history of distance education. But that doesn’t mean that we’ve meaningfully integrated its affordances– or ameliorated its pitfalls– into our online learning ecosystems.

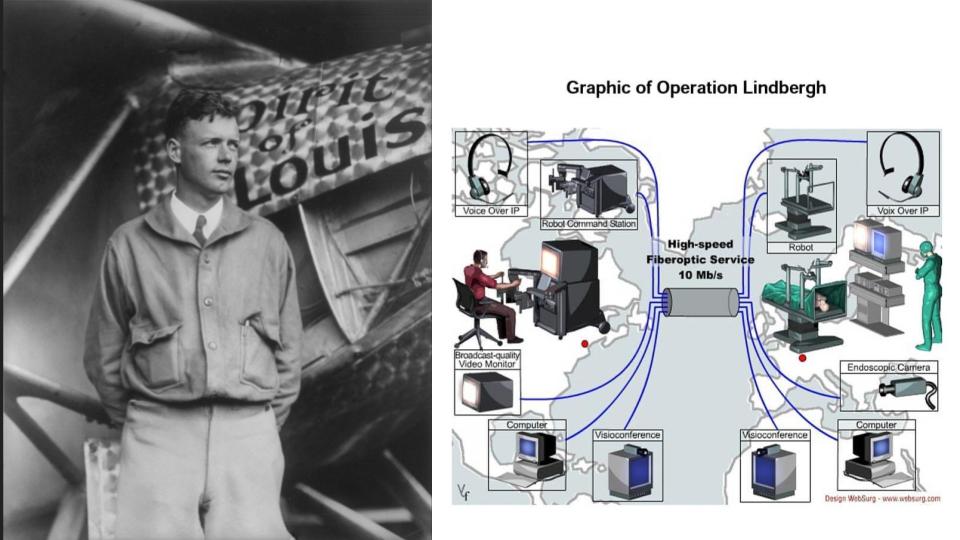

The internet is, as I am most interested in it, a technology that connects. But connective technologies have existed probably since the dawn of technology (choose any date for that you like, going back to the stone age or whatever). Charles Lindbergh made the first transatlantic flight in May of 1927, flying from New York to Paris in the Spirit of St. Louis. While humans had other ways to connect the continents, this was a new, important way to bring a human body from one part of the world to another. Nearly 200 years later, in 2001, the first telesurgery operation was conducted. A doctor in New York removed the gallbladder of a patient in France using an internet connection and a robotics set-up. I am sure because it would one day make a meaningful comparison for this keynote, that telesurgery operation was called Operation Lindbergh.

The press release for the telesurgery posits that some day (which day, by the way, is here) the internet could provide a sort of umbilical cord to link a young surgeon with more experienced teacher surgeons.

Of all the phrases to choose (like tether, link, connection, wire, bridge, whatever!), they chose the umbilical cord. If only the gallbladder surgery in Operation Lindbergh had been the delivery of a baby instead, then this keynote would really be on fire! Because we want so very badly to believe that the tethers, links, connections, cords that technology provides us in communication and in teaching can be human, can birth not only knowledge, but more humanity.

But how is our humanity served if we continue to think of the connective tether as a line? A line generally moves in one direction, with no width to allow interactions along its axis. At the end of the Operation Lindbergh press release, there are other dreams of how telesurgery could improve the future. One is that “It would also make it possible for developing nations to benefit from the expertise of world-renowned surgeons in order to enhance care in their country.”

So many assumptions here about where medical knowledge resides and who has the capacity to teach and who must be lucky enough “just” to learn. Position this against last month’s headlines about medical care inflected by missionary zeal and the fatal effects it had on the communities who were supposedly being served, and position it against a complex colonial history in which medicine and the manipulation of bodies played a pivotal role in shaping the oppressive poverty that challenges many “developing nations” today. When the web flows one way, we get a power dynamic that doesn’t increase learning as much as it increases control.

And the culmination of the dream: fully automated telesurgery, from pre-op to popsicle. I don’t know. Health care in the United States is a train wreck on a bunch of levels (most related to markets), and who am I to say how we should improve it. Maybe robot doctors are what we need. In 2001, we could barely imagine past these dreams, to an even more glorious time when there would be no human doctor at the end of the umbilical cords, when AI would do the thinking and the internet would communicate, and the robots would do the physical surgery. These connective technologies started out from histories that obscured and constrained human connection and they look ahead to a utopian future that all but erases human connection altogether. And we call it personalization, learning, healing.

Part Two

We recognize the disconnection in connected learning, and there are lots of ways we try to humanize our online classes, most of which are really helpful and lovely techniques. But also I marvel that education has grown up as something dehumanized, dehumanizing, not only through the straight-line constraints of the distance and personalized learning trajectory, but through the industrial-age contexts that supported that trajectory as it fed the factory-line model we’ve inherited. (See Cathy Davidson’s The New Education for more about this.) So now we are in this awkward positions of being humans fighting with machines and structures in order to stay human.

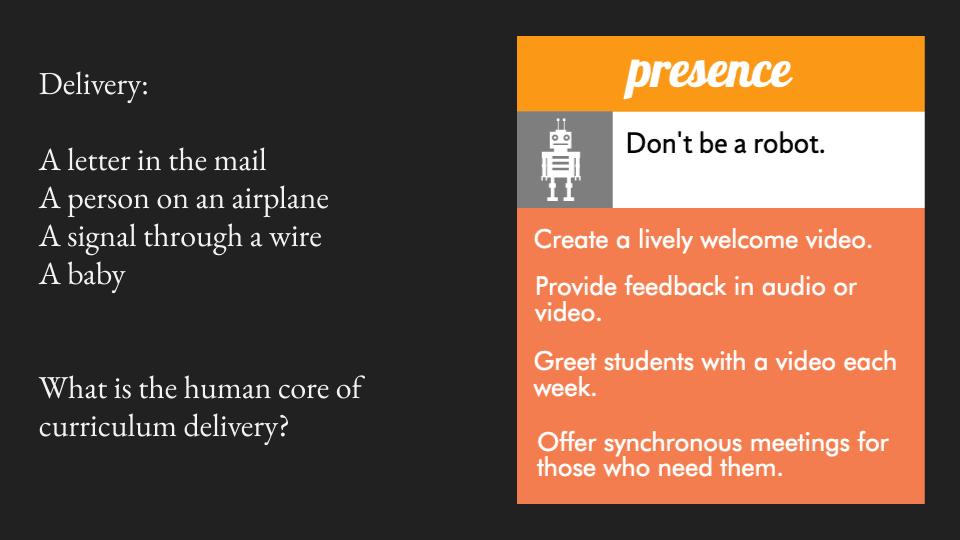

Let’s take a look at curriculum delivery, that deeply personalized, highly scalable holy grail of online learning. Delivery is a familiar word in the kinds of paradigms we’ve been examining so far, but even in our birth metaphors, the implication is that delivery is better when it facilitates a straight line between two parties. Those of us troubled by the dehumanization of personalized curriculum delivery work hard to add a personal touch to our curricular designs.

My favorite work on this is currently from Michelle Pacansky-Brock, an art historian and community college professor who is a role model of mine in faculty development work. But I want to see Michelle’s ecosystem’s emerge out of the box, off the line. I want to know what happens not when we try not to be a robot, but when we encourage ourselves to connect like humans.

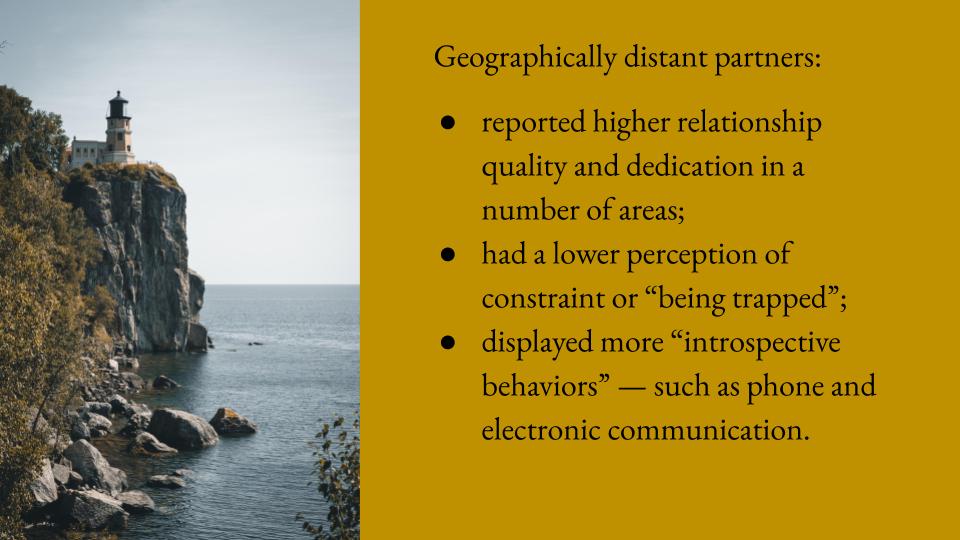

You know what? Long-distance relationships work out better than you might think. I dug into some research and it seems that we compare long-distance relationships against “normal” ones (or whatever you want to call them!) and assume they are shadows of the original. But in fact, long-distance relationships have several qualities that are really unique and seem like healthy qualities for a relationship.

LDR’s “reported higher relationship quality and dedication in a number of areas; had a lower perception of constraint or “being trapped”; and displayed more ‘introspective behaviors’ — such as phone and electronic communication.” Interesting to think of these in online learning. We appreciate the way that online learning frees us from the constraints of time and space, and we appreciate the reflection that can happen when students don’t always have to think quickly in real time, but can reflect on the material at their own pace and from their comfort zones. But perhaps we underestimate the ways that this can enhance the quality of learning itself.

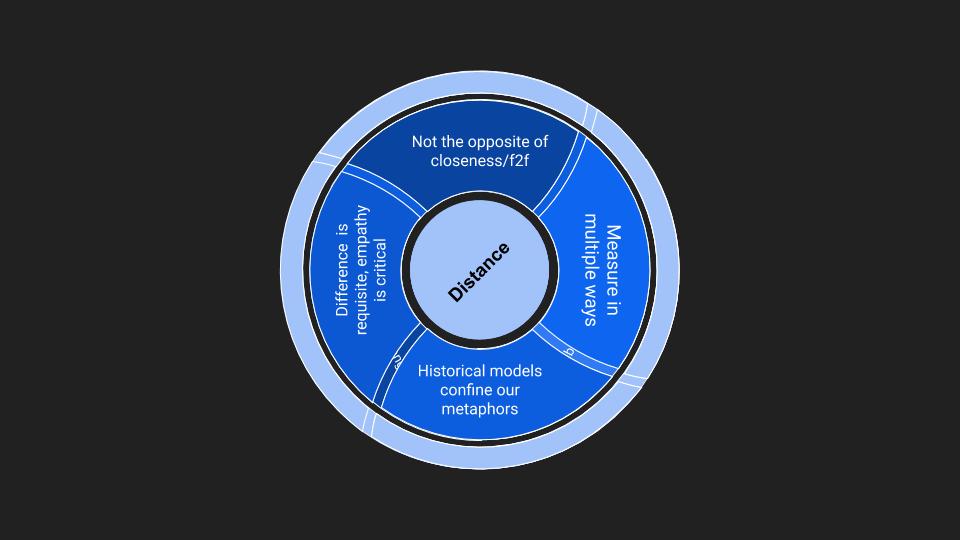

The next part of the presentation attempts to map out a different constellation of thinking about distance in distance learning, and a new set of architectures for learning that develop from this constellation. In part, I refuse the metaphors that we ourselves have generated through our industrialized, regimented, linear (not to mention colonial, racist, classist, sexist) historical education timelines. I don’t refute them; I acknowledge and resist them. Because the historical models we’ve inherited and sustained confine the metaphors we work with when we imagine what online learning could be.

Does distance have to be the opposite of closeness? Is online the opposite of face-to-face? I contend, after Maitland, that silence is not the opposite of language, and that if we think of distance more creatively, we can release it from the dichotomy that pins it to its second chair, always a sidekick to the real thing, our face-to-face experiences.

Distance asks us to measure and describe our relationality and this can be done in many ways. Even quantitative metrics are not singular. Being far away is also a way of marking a kind of proximity, as when [A] waved to [B].

When we think of distance as an invitation to explore our relationality to others, we invite ourselves into a learning community, and this is a precious resource and an opportunity.

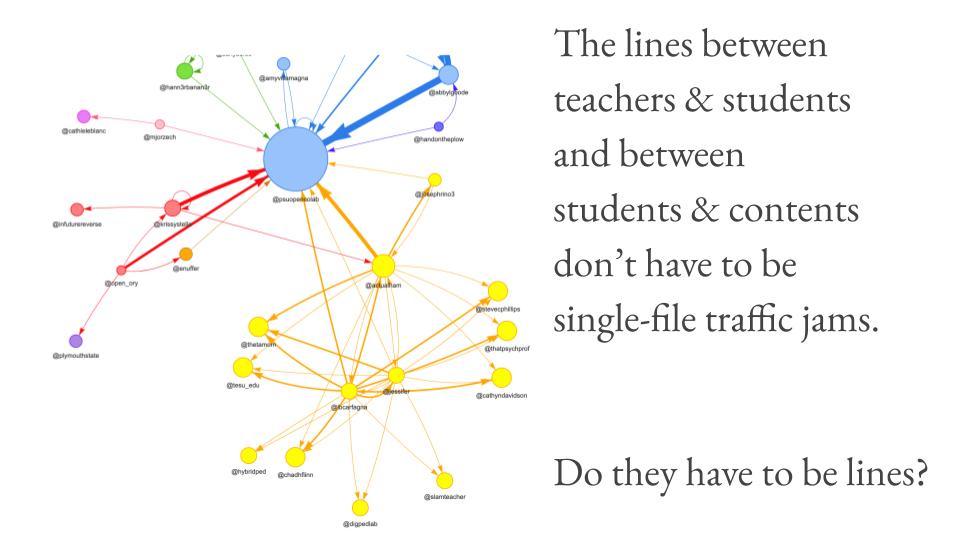

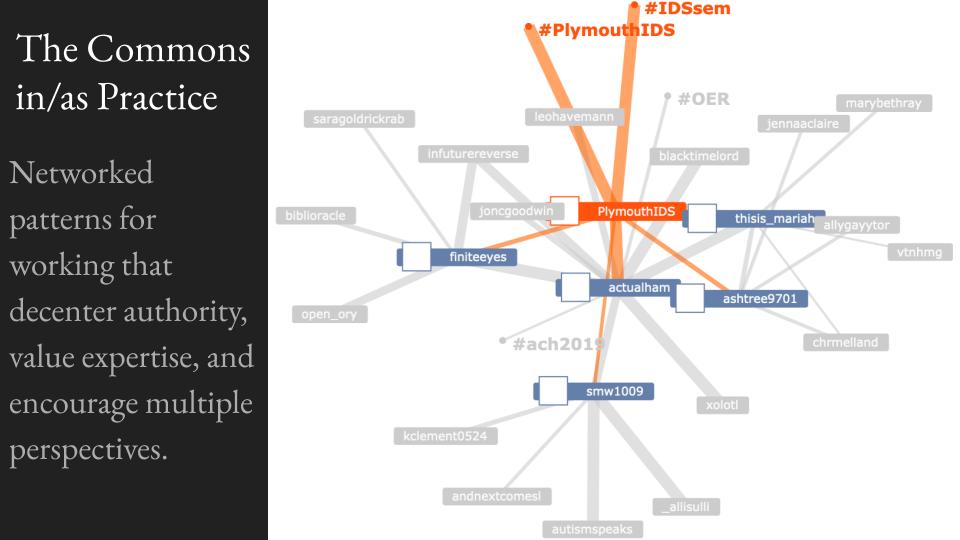

This is a dataviz of a tweet patterns in a new learning community coordinated by @PSUOpenCoLab. Or is it two learning communities? Or more?

The web is called the web, and not a line, but simply put, our learning architectures are built for the simple-line correspondence class and the push-button binary logic of a teaching machine. What does learning look like if the lines become a tangle? Or what my friend Dave Cormier calls “a rhizome?” What happens to knowledge?

To webify the web, we need to move past thinking only about the affordances of “digital” tools, and look at what connection in education really offers us. Just four slim years after Operation Lindbergh was dreaming about fully automated telesurgery, George Siemens was thinking about how the internet would change not only how we learn, but what we learn. Since when we connect learners and allow them to learn with each other collaboratively (not just from each other in a linear no-passing zone), we change the shape of knowledge. A good basic example of this is Wikipedia, where the fullness of an entry can transcend the expertise of any one editor or contributor. George explores how the web can connect people, but also how people can create nodes that engender new knowledge that originates not in any one person, but in the connection itself.

But how do we keep connected and connectivist approaches to learning from dehumanizing us, from disempowering and excluding, from automating us into oblivion or into an even more digitally divided society?

If you think I will have a simple answer for you, you may as well toss down your oxygen tank and head back to Everest base camp now right now, because there is no summit here. But I will share with you one of the concepts that has been helping me develop new practices with my students and faculty colleagues.

The commons is a vast concept, and I have no interest in pinning it to distance education, or in solidifying its definition. But for the purposes of this talk and for the purposes of my most recent work, I am thinking of it as:

You may have heard of “the tragedy of the commons.” The phrase was especially popularized in a 1968 article in Science by ecologist Garrett Harndin, who cites an example from 19th century economist William Forster Llyod about overgrazing. Look– here’s a nice meadow. It’s lush and green. It’s open, a shared resource. Let your cows in! But of course, the greedy guy with the most cows gets in there and grazes the hell out of the meadow and it totally dies and everyone is out of luck and the cows are hungry and this is why we can’t have nice things. The tragedy of the commons. But the commons there is a resource. But the way I and a growing group of open educators have begun to think about it, the commons is not a thing or set of things. Commons, as my friend Jim Luke is fond of saying, is a verb. Overgrazing happens when sustainability and sharing are not the fundamental points of the commons: instead free stuff is the point. How do we make learning less about getting and giving free stuff, and more about the freedom to think as widely as our minds allow?

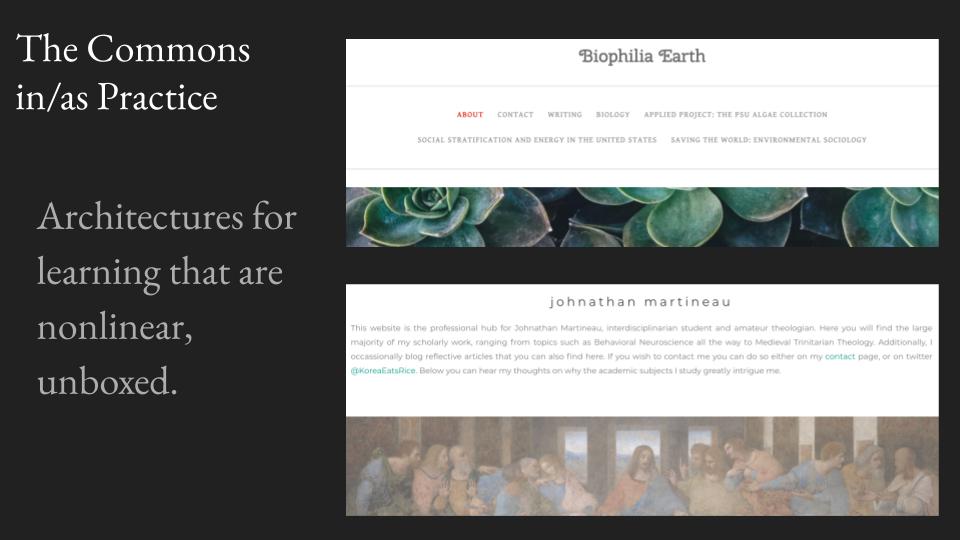

Here are some of the practices I have been working on with my students to begin to think about how teaching and learning might look if we attended to the values of the commons: the freedom to think and work in an ecosystem that centers respect, sharing, access, and justice. First of all, I try to think outside of lines and outside of boxes. The biggest line is the syllabus schedule, and the biggest box is the learning management system (the lines and boxes may be different for you in your job). But I stopped assuming that learning outcomes could be fully prepared in advance of meeting learners in a course. I stopped choosing every single reading in advance, and stopped crafting every assignment before I had input from students. I stopped wrangling in digressions as if they were a distraction from the content. This changed the shape of my courses and started to change the shape of the work my students were doing. We quickly outgrew the LMS, where students had trouble customizing and sharing the ideas that were starting to feel more like their own. I could no longer in good faith import my LMS course into the next semester and flush away all of the student work without feeling like I was losing valuable insight for the next cohort of students. We cobbled together ways for students to create new systems of their own to manage and catalyze their work. Over three years, that evolved into the adoption of Domain of One’s Own, and you can see from these two examples (from Rebecca and from John) that students still work in ways that seem recognizable, but that freeing them to direct their own learning and design and control their own connected websites changed significantly what our course looked like and what it created.

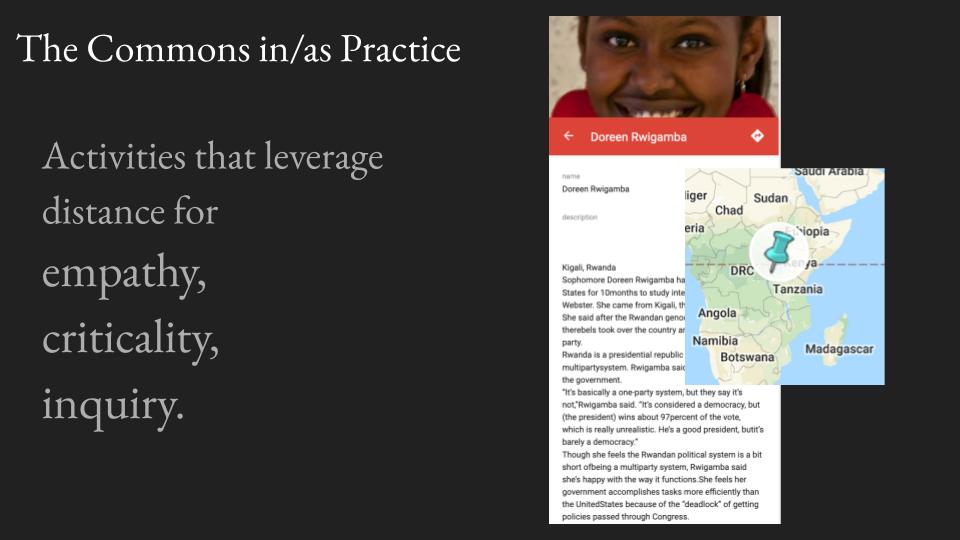

I was inspired early on in this work by a colleague of mine at the University of New Hampshire who used MyMaps with students in their English as a Second Language course. They built a course map together, and when students went home for spring break, they created video tours of their hometowns all around the world, and this map not only allowed them to practice their English, it also allowed them to share their culture with each other and with their American college.

The project you see here is a project from Webster University on the political dimensions of world religions, and students write papers and share video and key sites pinned to a map to explain the political dimension of religious dynamics in countries that they know intimately as home. This work is not hoop-jumping. It has the potential to be deeply impactful both for learners in the course and for various publics outside of it, and work like this approaches distance learning thoughtfully, uses distance as an affordance, and leverages distance as an opportunity to let people tell their own stories and be heard in their own contexts, even as they connect across the world.

So going back to networked learning… This is a dataviz of our Interdisciplinary Studies program on Twitter. It’s summer, and this only captures the last couple of months when many students aren’t in session, but you can see our program surrounded by our professors who are surrounded by our peer mentors who are surrounded by our students who are surrounded by various nodes of public collaborators. And all of that is great. But it’s those nodes where the magic happens, where students are connecting their academic work to communities outside our institution (this is in your college’s mission statement, I guarantee it).

The more I teach to facilitate these bursting ancillary nodes, the more I end up working to decenter the big hubs in the middle: the program, the teachers. Lots of faculty bristle when we talk about learner-directed curriculum, de-centering authority, and even sublimating content to the more important act of connecting. When content is king, we have to bend to its will, but when connection is the coin of the realm, then we learn through the work and the dialogue. This can mean you don’t hit all of the precise points along the way. You may lose your spot in line up the mountain, but it turns out a ton of people have already been up Everest– there’s a ton of garbage up there to prove it–and there may be something worth learning if you stop near basecamp to talk with locals who are working to clean up the mountain.

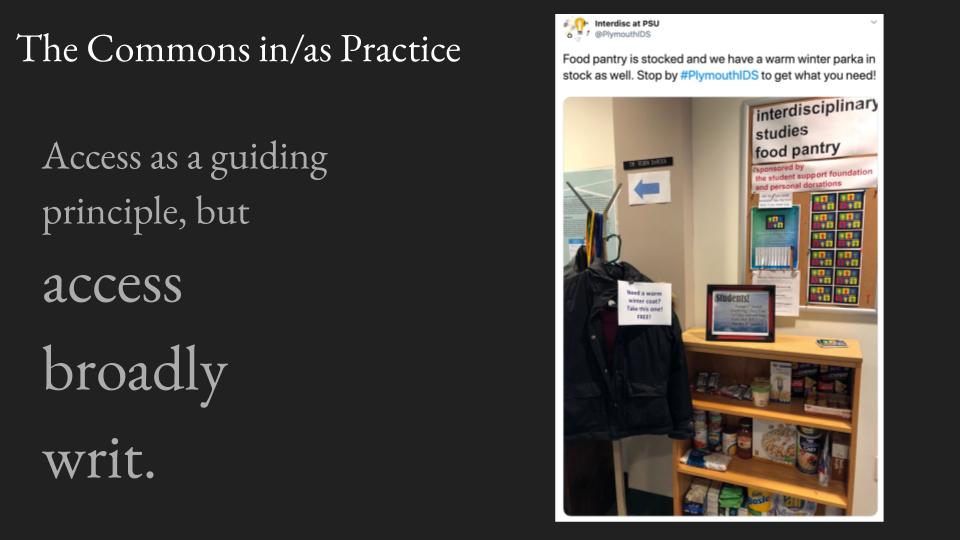

The internet helped me imagine an unboxed learning world, it helped me understand how connection can shape content and how distance can fuel inquiry and empathy. But the internet is no panacea for anything, and the commons doesn’t live in the internet. The commons is a way we commit to shaping the internet. Where I teach, many students have trouble affording laptops (and especially good laptops, and by that I mean laptops that work). Many have trouble affording broadband at home or paying for data for their phones. Online learning isn’t an easy option for someone in the rural New Hampshire North Country, where broadband access– and sometimes even electricity– is unreliable or nonexistant. But thinking about a commons-oriented approach means that I want a web that’s accessible to more learners. And a web that doesn’t use its communication capabilities to surveil or police the bodies of my black and brown students. I ask critical questions about the tools I choose to make sure I understand how to give students choice when they lack tech access and how to help them understand the risks of sharing their data, their identities, and their ideas with a world that is, now as much as ever, hostile and violent to certain people, especially people of color, women in particular, and queer people, and immigrants, and disabled people and people who’ve crossed a familiar border on a regular Saturday morning to shop at Walmart. Once I started caring in my practice about access to technology and critical approaches to technology adoption, I realized that what I really cared about what access broadly writ.

This meant caring about all the things that kept my students from coming to the table to learn: among the main ones for my students are food insecurity, homelessness, childcare, disability issues, lack of transportation, mental illness– so many of these deeply inflected by poverty, racism, ableism, domestic violence, and their experiences in the military. To build a commons-oriented internet is to realize that the commons is not about the internet. Accessible technology and technology that engenders collective approaches to learning are part of an even larger set of values: that the public good is enriched when every learner has the access to shape the world. To do that, our faculty and instructional designers and librarians and technologists and really all of us: we all have to care about what barriers people face in joining this learning community, and whatever our training or job description, we all have to take responsibility for all of the barriers that put walls between our students and this collective vision.

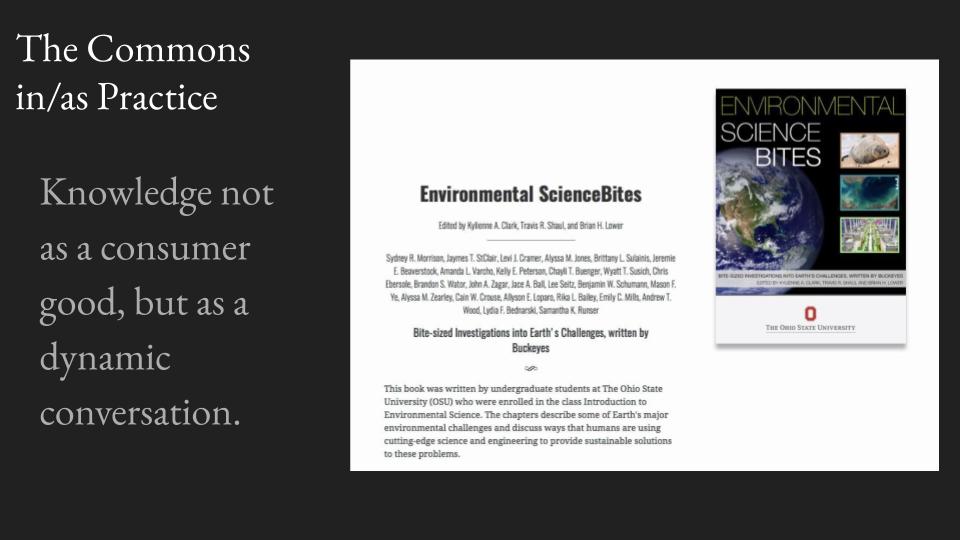

This is a companion textbook that Environmental Science students at The Ohio State University created as a team. It’s openly licensed and easily expandable from year-to-year. It involves a new generation of scholars in the world’s most pressing climate and environmental issues, and helps those new to the field learn from peers who explain and inspire in terms that make sense.

Work like this dramatically changes the concept of “access to knowledge.” Because like the commons, knowledge is not a thing. It’s a dynamic flow that shifts minute-by-minute as new perspectives re-see the familiar. Students are key to this dynamic, and so valuable in helping to illuminate the cracks and fissures in the doctrine of a field. Involving students in knowledge revision and creation is not a charitable act, or even strictly a pedagogical one. It is a way to recognize that the web has changed how we know, and we have an opportunity to shape our learning designs around that. This can help us build a web that is better for learners and better for learning.

Well that was a rant, a ramble, a rhizome maybe? I tried to make a concluding slide, but it wrapped it all up too neatly, and really I just want us all to go away to talk together about what gifts distance gives us, what troubling legacies of learning shape the courses and institutions we offer to our students, and what role the public and the public good play in how we think about education.

Does the school or tool or company that you work for or with start with learners, empowering them to shape and revise the markets that serve them?

Does your school or tool or company leverage technology to support the full potential of human creativity and connection?

Does your school or tool or company scale its benefits not to serve profit but to open access to learning?

Does your school or tool or company keep people and their diversity at the heart of personalization?

We have to reconceptualize the vision that powers our uses of the web in teaching, and align that vision to our practices. The horizon looks like a line from here. But maybe it doesn’t have to be one.

Further Reading & Works Cited

- Assie-Lumumba, N’Dri T. Cyberspace, Distance Learning, and Higher Education in Developing Countries: Old and Emergent Issues of Access, Pedagogy, and Knowledge Production. International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology, 94. BRILL, 2004.

- Bloom, Paul. “Against Empathy.” Boston Review, 20 Aug. 2014, http://bostonreview.net/forum/paul-bloom-against-empathy.

- Brocansky, Michelle. How to Humanize Your Online Class – 2 | Piktochart Visual Editor. https://create.piktochart.com/output/5383776-how-to-humanize-your-online-cl. Accessed 19 July 2019.

- Clark, J. J. “THE CORRESPONDENCE SCHOOL–ITS RELATION TO TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SOME OF ITS RESULTS.” Science, vol. 24, no. 611, Sept. 1906, pp. 327–34. Crossref, doi:10.1126/science.24.611.327.

- CNN, Shelby Rose. “American Missionary in ‘unlawful Medical Practice’ Suit after Babies Died in Uganda.” CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/03/africa/renee-bach-lawsuit-uganda-intl/index.html. Accessed 28 July 2019.

- Cottom, Tressie McMillan. Lower Ed : The Troubling Rise of for-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. 2017.

- “Does Empathy Have A Dark Side?” NPR.Org, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/04/12/712682406/does-empathy-have-a-dark-side. Accessed 21 July 2019.

- Hathcock, April. “My Trauma Is Not Your Thought Experiment: On Oppressive Empathy.” At The Intersection, 15 June 2018, https://aprilhathcock.wordpress.com/2018/06/15/my-trauma-is-not-your-thought-experiment-on-oppressive-empathy/.

- Jan05_01. http://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm. Accessed 28 July 2019.

- Kitamura, Ryuichi, et al. Expanding Sphere of Travel Behaviour Research: Selected Papers from the 11th International Conference on Travel Behaviour Research. Emerald Group Publishing, 2009.

- Lindbergh, Charles A. Of Flight and Life. 1st edition, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948.

- Lindbergh_presse_en.Pdf. https://www.ircad.fr/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/lindbergh_presse_en.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2019.

- Maitland, Sara. A Book of Silence. Berkeley, 2008.

- “Mount Everest Cleanup: Sherpas Remove More Than 3 Tons of Garbage From World’s Highest Peak.” The Weather Channel, https://weather.com/science/environment/news/2019-05-22-mount-everest-cleanup-sherpas-3-tons-garbage-removed. Accessed 28 July 2019.

- Postmodern Parody: A Political Strategy in Contemporary Canadian Native Art. 1992, p. 8.

- Preciado, Paulina, et al. “Does Proximity Matter? Distance Dependence of Adolescent Friendships.” Social Networks, vol. 34, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 18–31. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2011.01.002.

- Stafford, Laura, et al. “When Long-Distance Dating Partners Become Geographically Close.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 23, no. 6, Dec. 2006, pp. 901–19. Crossref, doi:10.1177/0265407506070472.

- “Teaching Machines, or How the Automation of Education Became ‘Personalized Learning.’” Hack Education, 26 Apr. 2018, http://hackeducation.com/2018/04/26/cuny-gc.

- “The Advantages of Long-Distance Relationships.” Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/why-bad-looks-good/201903/the-advantages-long-distance-relationships. Accessed 1 July 2019.

- Trostel, Philip A. “The Fiscal Impacts of College Attainment.” Research in Higher Education, vol. 51, no. 3, 2010, pp. 220–47. JSTOR.

- View of Examining the Impact of Video Feedback on Instructor Social Presence in Blended Courses | The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1821/2909. Accessed 19 July 2019.

- Watters, Audrey. “Draw Me: A History of MOOCs.” Hack Education, 20 Jan. 2015, http://hackeducation.com/2015/01/20/draw-me.

I think the issue is not human centered or content centered, but how to merge humans with content.

In my experience the best instructors are concerned about their students, their subject matter and the job of teaching. They show these attitudes in their instructional design and their interaction with students. They commonly follow a set of instructional principles that are in accord with their attitudes of concern.

I love the idea of rethinking ‘distance’ in distance learning! It’s so much more than just physical separation—it’s about creating a personal space for learning that’s tailored to individual needs. In a way, distance learning gives students the freedom to curate their own environment and learning pace, which can actually make the experience feel more personal. Instead of being confined to a classroom setting, learners have the opportunity to shape their education in a way that fits their lifestyle. It’s a new way of thinking about how we engage with knowledge, and I think it’s an exciting evolution in education!