In this post, I am going to describe #Opensem, an Open-Pedagogy-powered First-Year Seminar (FYS) that I taught this past Fall at my small, public university in New Hampshire. While following certain parameters set by the university regarding learning outcomes and goals for the FYS program, I ran the course as an experiment in radical OpenPed. I say “radical” not because it’s anything brand new or particularly edgy, but because it takes some of the basic principles of Open Pedagogy as I have been conceiving of them and puts them into practice in the fullest ways that I could imagine within the confines of my institution. Open Pedagogy offers so many possibilities for K12 teachers and college-level instructors, and most faculty will not find it suitable to their courses to adopt all of the OpenPed approaches that this course drew from, but I thought it would be helpful even to those who want to moderate their implementation of OpenPed to have an example of what happens when you push to the more extreme ends of the OpenPed continuum.

Defining “Open Pedagogy”

Part of the ethos of working “open” to me is to resist static definitions, since one presumption that open makes is that knowledge is always changing shape. That being said, it’s helpful to have a sense of the working definition that I was starting with at the outset of this course in September 2016.

I thought of Open Pedagogy as comprised of four basic guiding ideas:

- Open Pedagogy improves access to education, but this is access broadly writ. We start by thinking of how OER drives down textbook costs, and note the impact that book costs have on student success (course throughput rates, for example). But we don’t stop there. We look at the issues raised by converting to digital materials (digital divide, access to devices, digital redlining, accessibility and universal design, etc.) and consider our pedagogies in relationship to every access issue we encounter as we teach.

- Open Pedagogy treats education as a learner-driven process. Though we note the frequent marketing use of phrases such as “student-centered” to describe the classroom experience and course organization, we note that these phrases are often hollow, ill-defined, or attached to low-bar student involvement guidelines. Open Pedagogy asks as to rethink every aspect of the courses we build to consider how students can be empowered to move into the driver’s seat.

- Open Pedagogy stresses community and collaboration over content. While acknowledging our own expertise as subject-matter scholars and the importance of the content that we cover, OpenPed works to connect learners to their fields, peers, colleagues, and mentors via healthy networks so that they can draw on those communities to continue learning past the end date of the course. This actually works to enhance content transmission over time, since much field content changes rapidly.

- Open Pedagogy connects the academy to the wider public. We work to merge theory with practice, engage learners with “communities of practice” that matter to them and to the world, and make the educational system work for both students and the public good.

Don’t like those? Yeah, I might not, either. The slide with my OpenPed definition changes every time I give a presentation about it. Which is cool. But at least it gives you a sense of the kinds of things I was mulling over as I started thinking about my FYS last summer.

First-Year Seminar

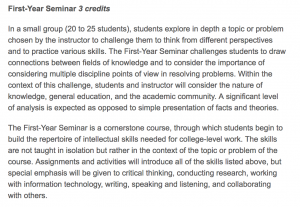

At my university, our First-Year Seminars are probably a lot like something you might have at your university or community college:

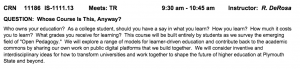

Each distinct section is organized around an individual question designed by a faculty member. Which of course, from an OpenPed standpoint, is already kind of a bummer. I wondered how to design a question that would allow students to craft their own question. Then I wondered what would happen if they all wanted to work on different questions; would that erode our community’s ability to collaborate? Then I wished they were all hanging out with me over the summer so they could help me figure out what to do. So that led me to create this question and course description:

I wondered if the course would ultimately be a course about OpenPed, or just a course that used OpenPed. Students picked their sections of FYS and I ended up with 25 students in my section. When I say “students picked their sections,” what I really mean is that they ended up in the sections they signed up for, but a grand total of THREE of my students reported actively choosing my class because they were interested in the topic. I think I can safely say that this means I had a pretty random sampling of my university’s first-year students, not particularly attached to the idea of rethinking education.

Building a Course Infrastructure

On the first day, I introduced them to the idea of “Open Pedagogy,” and explained that I was really hoping that the class would build a FYS based on what they all thought they needed to learn. At that class, I also explained that we would not be using our Learning Management System (our LMS is Moodle) much, but that they would each have the option to build their own websites –ePorts– where they could present and publish their work. Students went home and read articles by Audrey Watters and Andrew Rikard, and we then talked at our next class about issues involved with student ownership of the course management spaces. Students got set up with Twitter and Hypothes.is to use as course communication tools instead of Moodle and university email, and we talked about assessing the tools for usefulness as we progressed and deleting or changing tools as necessary.

It was honestly discombobulated. We started with no real place to work, and I realized that we could have spent the whole semester just critiquing the prescribed Moodle arena and building our custom LMS. Instead of doing that, I presented some key articles and let them choose to design ePorts or opt-out and stay in Moodle. They all chose ePorts, which we built at a reduced price with a special limited-time discount that existed from Reclaim Hosting (about $27 per student annually with domain protection). (Students can now get domains from my university’s Domain of One’s Own program, which are included in their tuition.) We decided to march forward with this trinity of tools (domains built with WordPress, Twitter for communication, Hypothes.is for online annotation), and use them as the infrastructure for our course.  You can check out some of our communications on our old hashtag, #opensem, which also became the nickname that we used to describe our course and our community as the semester unfolded.

You can check out some of our communications on our old hashtag, #opensem, which also became the nickname that we used to describe our course and our community as the semester unfolded.

I say “we” in that they had informed consent and opt-out possibilities and the freedom to work in other ways, but the reality was that I had a lot more knowledge in these areas, and most students were happy to follow my suggestions. Because all tools are ideological, it’s really loaded to lead students so forcefully into them; this is clear with the LMS and it was clear with my suite of tools as well. One reason I think institutions should talk about this stuff is that it would be helpful to have more courses participating together in OpenPed approaches, so then early courses could take (much) more time building a more authentically student-designed infrastructure and planning out how those infrastructures could work interoperably in future courses. Anyway, I would call the start to my OpenPed experiment exciting but also pretty-much a failure in helping empower learners to drive.

Costs and Access

The fact that the course was relatively inexpensive at $27 (which is, I should add, about $27 more than the fees in most courses that I teach), we did have a high rate of participation right from the get-go, with nobody left behind in the first weeks, struggling to afford a textbook. Some students did not have devices such as laptops or smartphones, but I had managed to get a grant from our faculty technology committee to cover the purchase of ten laptops that could be checked out from the library desk just a few feet away from our classroom. This did still present some challenges, since with so many disparate tools and accounts, it can be tough for students who keep switching machines (no autofill passwords, no bookmarked pages). We were always up-front about showcasing the places where access was an issue, and this class helped me make the case for DoOO, which will now allow me to completely drop the course fee (and the requirement that students have access to credit cards–ugh, horrible, and I apologize for not seeing the issue there). I’d like to see a laptop checkout policy that would allow students to check out machines for a week or more at a time (maybe for a semester); about 95% of our students have laptops at my university, so we should be able to find ways to more fully accommodate those who don’t. For those of you who teach in places where that percentage is much, much smaller, converting to OER or digital tools may augment the digital divide and increase costs for students rather than ameliorate the divide and lower costs.

It was also clear that the instruction to “create an account and play around in there” sounded very different to those who owned and regularly used technology and had continuous access to the internet, and those who didn’t. In another OpenPed class I taught this past Fall, I used peer mentors who staffed evening open hours to offer extra support to those who wanted to move slowly with the technology, and have a buddy next to them as they built and experimented. Despite me telling students that there was nothing they could break that we couldn’t fix together, it was anxiety-provoking for students who hadn’t used technology regularly and who had limited time to access devices and the web. #opensem didn’t have peer mentors, but it would if I taught it again. For #opensem, I basically just had continuous office hours. Because my office is in the library where our course was, and because I was in my office four days a week from 8am-9pm, it worked well for drop-in support, and many students sat and worked in my office lobby so they could pop in when they needed me. Honestly, I loved that. But you know, I can imagine that is not for everyone. Basic lesson– and you already know this– the “digital native” thing remains a garbage idea, and if you care about access issues, you will need to meet each student where she is in terms of comfort with tech. That takes time, and labor, and it may not be practical or feasible for you given your salary or circumstances.

Off We Go

So off we went, mostly well-enough-equipped and armed with a ragtag arsenal of discombobulated tools. We used GoogleSheets to track assignments and posts, GoogleDocs to collaborate on and crowdsource our syllabus and assignments, ePorts to present our work, and Twitter to talk to each other. I am not sure these specific tools matter much, but the fact is that the cobbled hot mess produced a sense that we were grabbing tools as we went in order to do stuff we needed to do, and we could see immediately that the process would be iterative and dynamic. Lots of our systems emerged together over the course of the semester. It makes me wonder if building a course management system is a useful part of any course curriculum. How much learning is lost when we template out the course architecture and mindlessly work to populate the blanks that open for us there? Did students benefit from having to build, critique, rebuild, and cope with the systems that we built as we went? I think so. We were always meta-aware of HOW we learned, not just WHAT we learned. For a FYS aimed at least in good part on helping students be successful in college, that seemed a very useful part of the course.

Collaborative Learning Outcomes

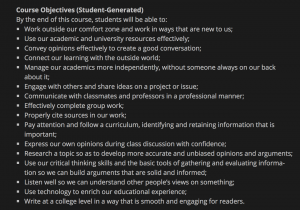

After we had some basic plans in place for how we would communicate and where besides our classroom we would work, we started talking about content. What should we learn in the course? I presented the latest version of learning outcomes that I had collected from the leadership of our campus-wide FYS program, and brought them to the table. We talked about them, and whether or not we should use them all (thank you, tenure– more about that later). Students wanted to use most of them, though we tweaked a few words here and there. Then I asked students to contribute their own learning outcomes, on the basic principle that learning outcomes for the course should not be cemented without participation from the learners. After making some brainstormed lists together, students blogged a bit about what kinds of outcomes were important to them. They ranged from highly skills-oriented, like this one from Jordyn Hanos, to those that leaned more toward connection and engagement, like this one from Skyla Dore.

We put all the outcomes we came up with into a GoogleDoc and students tweaked and revised and ultimately voted on them. I opened the online syllabus live at the front of the class when we finished and we updated the learning outcomes based on what they had created and chosen to upvote. Here’s what we ended up with:

Some of these I love. Some of them I would probably never have included myself. There are others I would have liked to have seen in here, but my suggestions were outvoted. I helped students understand that in our course, we would try to make the learning objectives guide our assignments, so that we were always working towards the things that we thought were important.

Some of you might be thinking that this exercise makes good sense in a FYS, where students are certainly qualified to help articulate what kinds of things they might need to learn in order to succeed in college. How could this work in a Physics course, an upper-level Latin American Studies course, a course on genetics for nurses? I think if instructors bring outcomes from accreditors and departments, and use their expertise to inform students about the kinds of content that will be crucial to their ability to move on in their learning, students can be asked to weigh in and contribute the kinds of ideas that only they would have. Students can be asked to contribute additional outcomes, or, better yet, they can be presented with the real requirements set forth by forces external to the course and then asked– just as faculty are asked– to wrestle with those and decide how they will be included in a way that feels compatible with learner-identified needs. Helping students see learning outcomes as inherently political, subjective, and worthy of critique seems to me a first step to helping them feel a sense of agency in their educational processes.

Student-Generated Assignments

Spending time on the learning objectives made a huge difference. Suddenly, we had a sense that the course wasn’t going to just be about OpenPed, but about how to prepare our group to succeed in college going forward. We set about designing assignments to correspond to learning outcomes. For example, one group worked up an assignment to help us work outside our comfort zones (Learning Outcome #1, which was one that students created and almost unanimously agreed was important). They outlined this assignment in a GoogleDoc:

Trying to get students outside of their comfort zone has been a challenge for years. This assignment is designed to see whether you can perform better when working in a work area that suits you. By reading the articles and finding out what could be your potential comfort zone it gives the reader a better understanding of what could come out of working in a place that they are uncomfortable or comfortable with. This skill is crucial in life to achieve your goals.

Students had a range of choices for this assignment, but those who liked this outline would click on the link below it and be directed to Jake McMaster’s ePort for the full assignment. Here’s Lissa Perry’s blog post in response to this assignment prompt. We built all of this week by week, with a syllabus that started almost completely blank and got filled in as we went along.

Cohesion, Collection, Curation: A “Textbook” Emerges

As the course unfolded, we realized that we were really looking most often at research and ideas about what could help students do well, particularly academically, in college. I introduced the diction of “retention” and “student success,” which was vocabulary that was new to my students. For all the zillions of hours faculty, staff, and administrators spend researching and designing programs around these concepts, we spend very little time talking with students about them directly. Opensem started to focus our assignments more deliberately around the concepts, and incorporate more research into our weekly plans. Students would find articles and post them on GoogleDocs, then pore through them to choose which ones they actually wanted to read and write about. Sometimes they read an article and posted critique and summary, sometimes they extricated quotes that other students could use in larger projects later. Ultimately, the combination of student-generated learning outcomes, student-created assignments, and student-curated readings and summaries began to produce a cohesive body of work that was connected both to the institution’s framework for the course and to the individual learners that were enrolled.

The work was, of course, dispersed across my own website, multiple GoogleSheets and Docs (some made my me, others by students), and the student ePorts. About three-quarters of the way through the class, I offered the idea that we could collate and collect our work into a kind of handbook of sorts, and offer that to future sections of FYS, both at our university and beyond. Students seemed excited that their hard work could be channeled into something that could have life beyond our course. I built a simple PressBooks shell for our work, and students divided into groups to tackle the different chapters that they wanted to write. This was so excellent, since it involved going back through the course and taking individual assignments and grouping them according to theme, and then ranking themes and posts to find out which ones we wanted to include. We also figured out where we had gaps and needed to do new research and write new content.

After about three weeks of collating, curating, editing, and writing, we ended up with OpenSem: A Student-Generated Handbook for the First Year of College. Every single piece of writing in it first appeared on the ePort of a student in the class, and every single piece of writing was connected to our student-generated outcomes and our student-created assignments. In cases where students openly licensed their work, I was able to do a simple cut and paste to bring that work into the “textbook.” When the ePorts were not openly licensed, students could either supply me with permission to use the work or choose not to be included in the textbook (these options were provided, but not ultimately needed since by the end, all had chosen to add some level of CC license on their ePorts). Every student who completed the course (including the one student who did not pass) ended up with material in the final book, even though we did not set out to make that happen on purpose. And here’s the magic: we offered this book up to the knowledge commons, and though it is rough and flawed in spots, it is a real contribution on many levels, to many fields, with application for many courses and future students. Public university students generating great work, sending it off to the public to use it as they wish.

Student-Generated Attendance Policy

Before I conclude here, I wanted to say a couple of words about course policies, and about grading. Students created their own attendance policy for the course. I’ve done this for four sections of classes across different courses so far, and the policy is always different. Sometimes it’s very strict, other times quite lenient. I’ve offered to have no attendance policy at all, but students have never chosen that option. This section chose this one:

We should strive for perfect attendance. If we miss more than five classes, our final grade will be lowered by 1/3 of a grade. If we achieve perfect attendance with no absences, we will earn the ability to convert one missed competency to a pass.

Say what you want about its flaws. I certainly did. But I will say that the four sections with student-generated attendance policies seem to have slightly higher attendance rates than the ones where I just had my imposed policy. Anyway, I could talk about this all day long. And then into the night. Suffice it to say that if you want to, you can ask your students what kinds of policies they think will help them learn. My experience tells me that they usually try to answer that question authentically, and they seem to know better than me what the answer is.

Student-Designed Grading Practice

I find grading to be very antithetical to the kind of learner-driven space I am trying to build in my courses these days. But I also choose to teach in a public institution where I have little ability to resist the culture of grading (I have made some structural progress in an Interdisciplinary Studies program that I direct, which will move fully to a P/NP system next Fall). In OpenSem, I decided to let students design the grading process. It took a couple of weeks (while we simultaneously did other things as well) to hammer it out. Basically, they designed a competency-based model where they would have unlimited time within the confines of the course to improve each assignment if it initially they did not “achieve the competency.” Achieving the competency would require them to meet all of the parameters of the rubrics, which were often designed by the students as they crafted the assignments. Competency would be achieved not at the conventional level of 60/Pass, but at more of a B level, with the idea being that as a connected course, we wanted all work to be share-able, and we wouldn’t want to share work that was just barely passing or below average because this would not be overly helpful to the knowledge commons or helpful to the student author who is trying to develop a readership or community of practice. In an OpenPed Composition section I taught, students had the ability to grade their own work using rubrics that we co-designed (the idea being that grading is a learnable skill just like anything else). OpenSem students did not want to grade their own work. They decided I would grade them, and they liked that arrangement as long as they could always revise after getting feedback and an initial grade. AGAIN, this topic could generate a 10-page blog post of its own. All I really want to say here is that OpenPed encouraged me to see every aspect of my course as open for rethinking and student involvement, and allowing students to help me set the grading procedures didn’t mean I couldn’t conform to the university’s grading requirements. All in all, the grading practice of the course led to a richer feedback model, a more collegial relationship between me and my students, and a low-pressure environment for learning. The grade distribution at the end of the course was not notably different from what I usually see in my courses, whatever that might indicate.

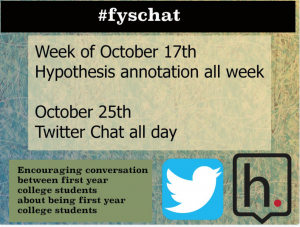

Connecting Students

In an effort to connect #opensem students with other learners outside of our course, we partnered with two other FYS sections at two other colleges. In collaboration with classes taught by Autumn Caines and George Station, we read an a rticle together, annotated it (check out the annotations here), and organized a day-long slow Twitter chat. You can read Autumn’s post here about how she and George got it off the ground. It was excellent all around, but I especially loved how my students were able to insert their own blog posts into the chat and immediately gain new readers and commenters, which added a thrilling dimension to their sense of authorship. This Twitter chat helped my students understand how to call external participants into their scholarship and thinking, and we used many of the lessons of that small collaboration as we talked about building Personal Learning Networks, working online in public, and contributing our own ideas to the knowledge commons.

rticle together, annotated it (check out the annotations here), and organized a day-long slow Twitter chat. You can read Autumn’s post here about how she and George got it off the ground. It was excellent all around, but I especially loved how my students were able to insert their own blog posts into the chat and immediately gain new readers and commenters, which added a thrilling dimension to their sense of authorship. This Twitter chat helped my students understand how to call external participants into their scholarship and thinking, and we used many of the lessons of that small collaboration as we talked about building Personal Learning Networks, working online in public, and contributing our own ideas to the knowledge commons.

Student Feedback

If this kind of info is important to you, the course evaluations were very positive. The course received a 4.4/5 for overall value and a 4.6/5 for contributing to the students’ intellectual growth. As an instructor, I received a 4.9/5 for “overall effectiveness,” which I find interesting considering how often OpenPed gets misunderstood as a pedagogy that deemphasizes teachers; I think OpenPed decenters teachers, critiques some kinds of teacherly authority, and binds learning to learners rather than to courses or instructors, but none of this means that teachers don’t matter or that we can’t be highly effective. Here are three comments from the evals that I think resonate in part with what I have talked about here:

We discussed what we all thought, as a group, was the most valuable to learn through this course. We worked through these skills all through the course and it helped very much being a first year student and new to this environment. We used new technology to learn. which made it fun and educational.

i thought the work was extremely helpful and I will be able to carry what I learned from this class with me in the real world. I wish more classes were set up like this!

I expected this course to be easier than it was.

I am hoping some of my #opensem students will write reflections on our experience (we got so busy at the end of class with our book, we just didn’t have time to do that as part of the class). If they do, I’ll link to them here.

A Word About Tenure

As I fervently conceptualize it, tenure doesn’t exist to protect lazy people. It doesn’t exist to protect bullies. Tenure exists to protect faculty who work on the cutting edge of research, who speak knowledge to power, who critique their institutions so they will better serve students and the public, and who take risks in their teaching in order to facilitate learning. I feel pretty happy with how #opensem turned out for those of us who were part of it, but when I started and at certain points along the way, I was aware that it could have imploded on a number of levels. I believe– I want to believe– that my tenure offered me the protection I needed to take these risks. I am aware that tenure is tenuous all across the U.S. right now. I am also aware that many of my colleagues in the contingent labor force don’t even have basic tenure protections at all, tenuous as they may be. Assess your level of risk before you take these risks with your teaching (or your writing, or your online digital and public identity). And those of us with tenure protections must fight to extend them to those who need them, defend them against those who would strip them away, and resist new HigherEd cost-savings measures that “innovate” without consideration for the importance of academic freedom to teaching and learning. Just a short word to those who like these ideas but don’t feel safe enough, for many reasons, to try them: I see you, and you are right to be both cautious and angry.

tl;dr

Your students can work with you on course learning objectives and policies. They can help build a course management system to organize the learning and work. They can design assignments and a grading process. They can curate readings and other course content to shape what they learn, within whatever given parameters exist. They can publish their research to help them connect with their communities of practice, and they can publish educational materials to help the next generation of learners. As a teacher, you can do all or some of these things, depending on what you think will best serve your students and their diverse identities and circumstances, your academic discipline(s), your institution, and your sanity. And you are not alone. I jumped in with two feet over the last year, and I am happy to share my mistakes and challenges, as well as stuff that led to the moments of joy that enlivened me along the way. Tweet me and let me know how I can help.

Sorry this is rambling, but classes start next week and I got things to do! Wishing you a great semester, filled with learning outcomes you couldn’t begin to plan for yet.

My thanks to the following for inspiring me with specific work that has informed both #opensem and this post:

Chris Gilliard on digital redlining.

sava on how open tends to privilege the privileged.

Gardner Campbell on personal cyberinfrastructures.

On student-centered grading practices, I draw from Cathy N. Davidson, Dave “just because we have to assess it doesn’t mean it can be assessed” Cormier, Chris Friend, Jesse Stommel, and Starr Sackstein.

There are a lot of people who have contributed to my ideas about OpenPed, but here’s just a short list of people whose links I ALWAYS CLICK because they make me think: Rajiv Jhangiani, Maha Bali, Remi Kalir, Catherine Cronin, Kate Bowles, Michael Caulfield.

Brilliant, brilliant stuff Robin. I can’t imagine an course more suited for OpenPed than a first year seminar. The quote from your student matched what I saw from teaching DS106 at UMW; it was usually like “This class was way too hard for a 100 level class” or “I did not believe this class would take this much time” — 90% of them had a following “but” that cited how much they got out of the experience. And for a few they kept their blogs, or tweet me, years later I get to see what they are doing.

A useful thing I did at the end, rather then the usual course feedback, was something I learned from Martha Burtis, she called it the “Pay it Forward” assignment. The idea was to ask them to create something in media (video, audio, or visual) along with a post that is meant to give advice to future students. It never failed to amaze me how it transformed the typical feedback where they try to tell you what they think you want, to what turns out to be very self reflective.

Also, thanks for using my pix! Some I know well, and some I forgot 😉

I forgot to write about the end of the course– students did give Ignite Talks! A few posted them on their ePorts, but most did them live so they didn’t leave a record (we didn’t film them). Some of them were really great, but I especially loved the tweets that came out of that class as they watched each other. That was a neat final project in lieu of an exam. I think I could do it better second time around, but the Ignite format was kind of neat for that kind of course synthesizing. I love the “Pay it Forward” idea, and that would have likely produced some great stuff to fill out the book… Thanks for reading, Alan! And thanks for all of your beautiful slides, and so well tagged– they are a dream to work with!

Fabulous article Robin. Inspiring. I was directed to it as part of an Open University course I’m undertaking. I ‘teach’ an introductory study skills module in a 3rd level college in Ireland. As part of that I do some work around student transition & transition. We have tried a number of things but the students struggle with the study skills module itself (as well as the transition to 3rd level!) – there are a number of reasons for this – so I loved what you did. Particularly with getting the students to help construct the Learning Outcomes. How did you get them to do this – to engage in this discussion? Might sound a simple question to you but with our students they tend not to ‘know what they don’t know’…. Their self efficacy is quite high and experience tells us that this does not translate to the work that they produce or the effort that they put in. Having come through school they think that they ‘know it all’… so it becomes a difficult progress to get meaningful engagement.